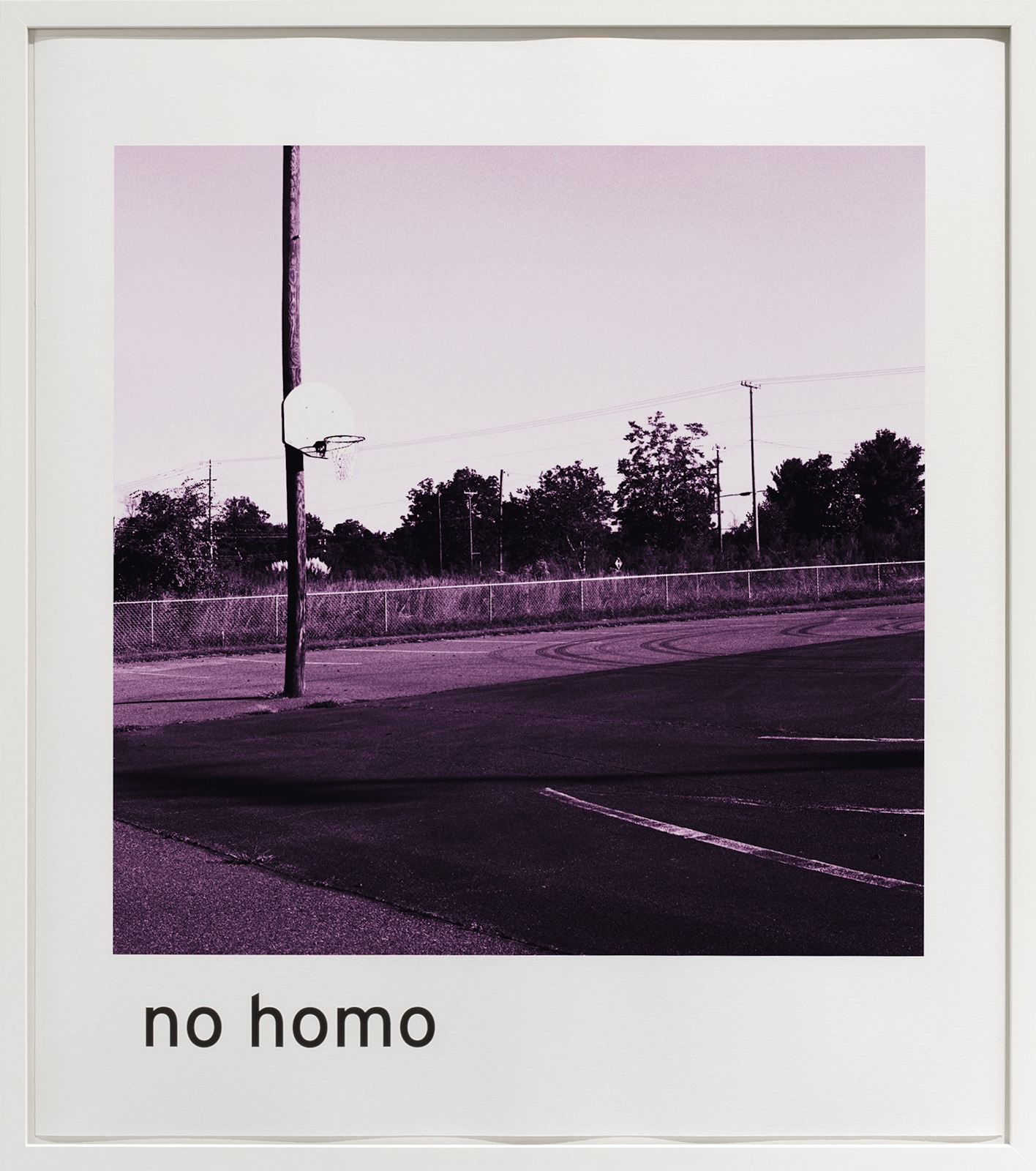

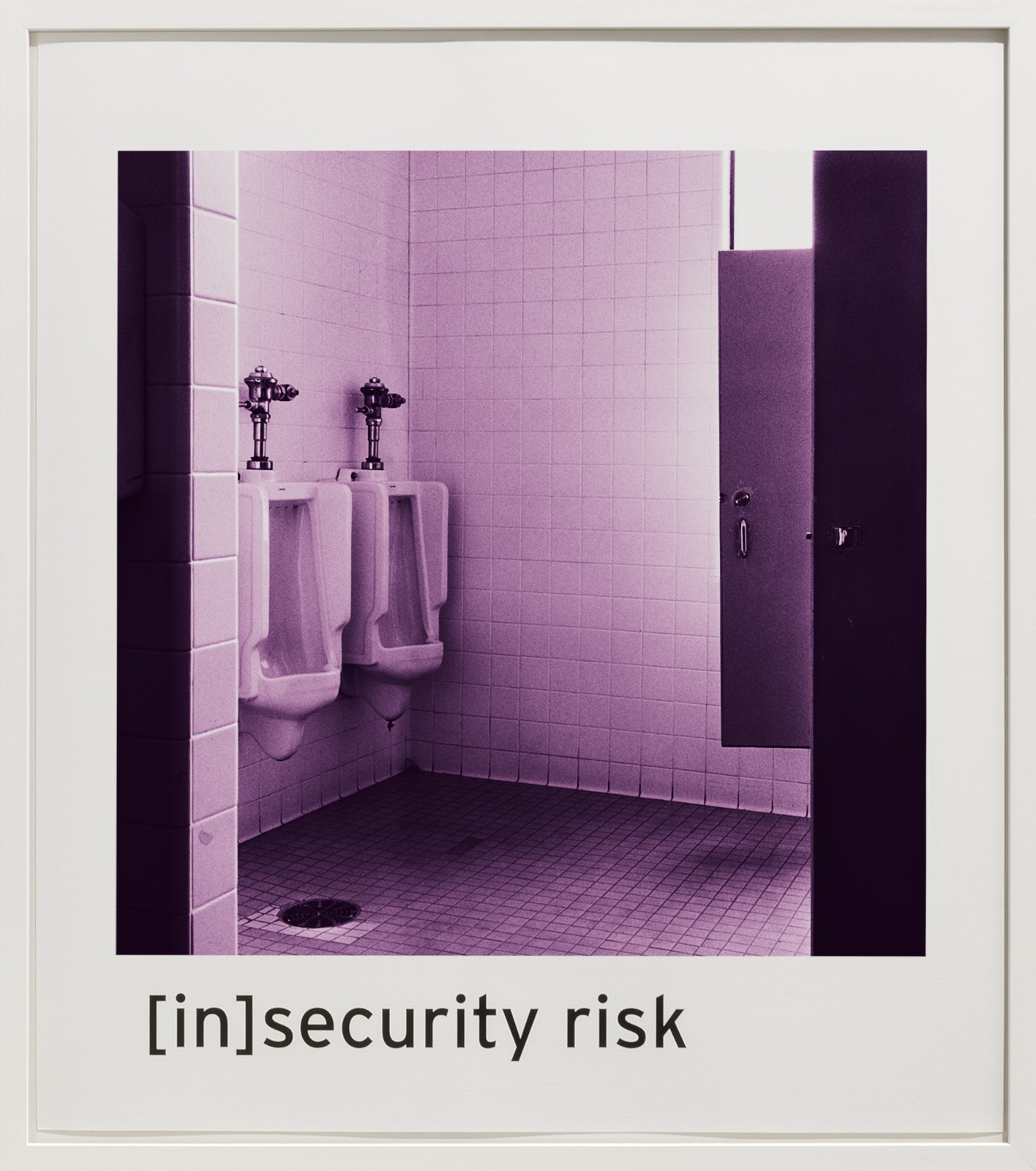

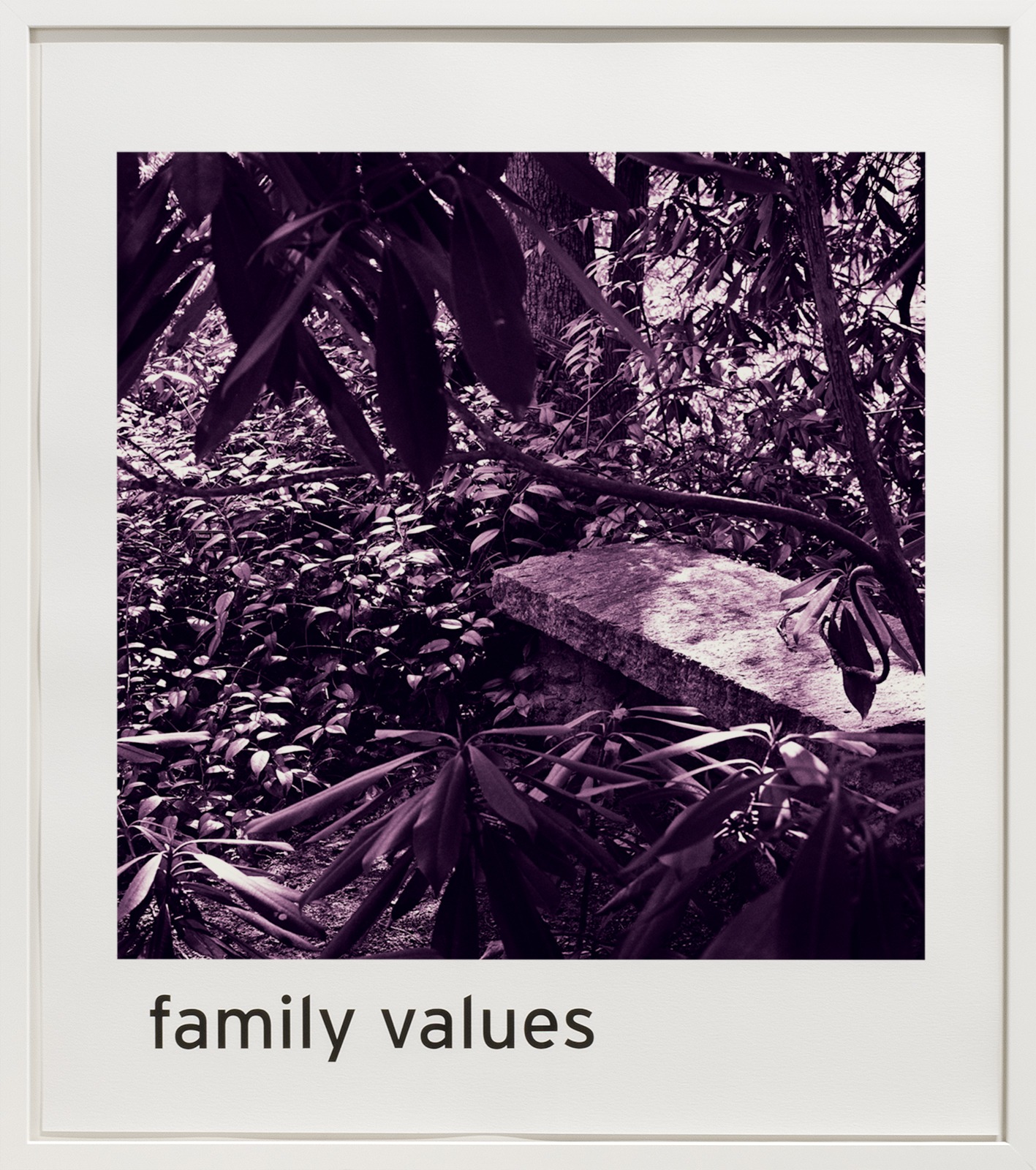

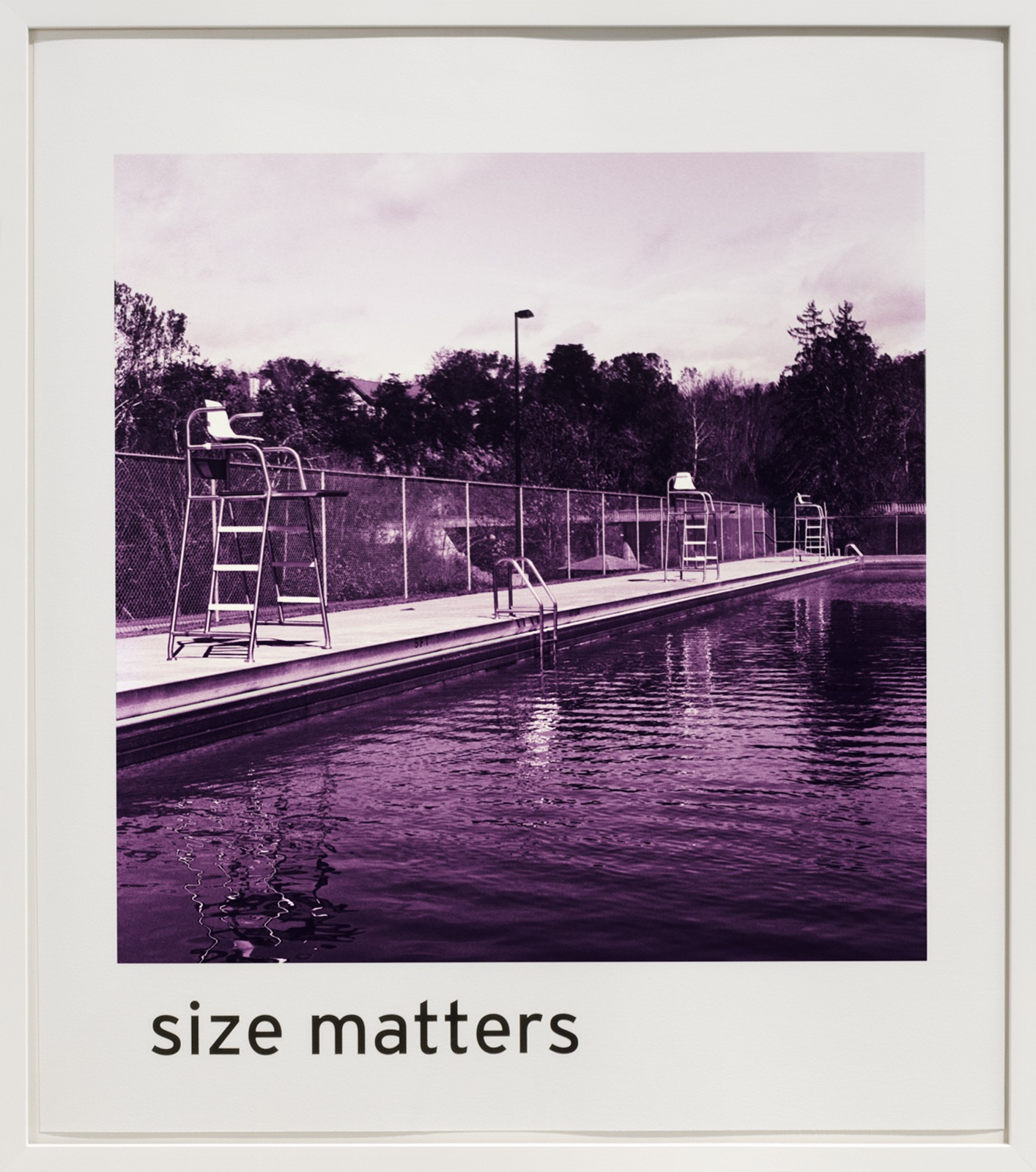

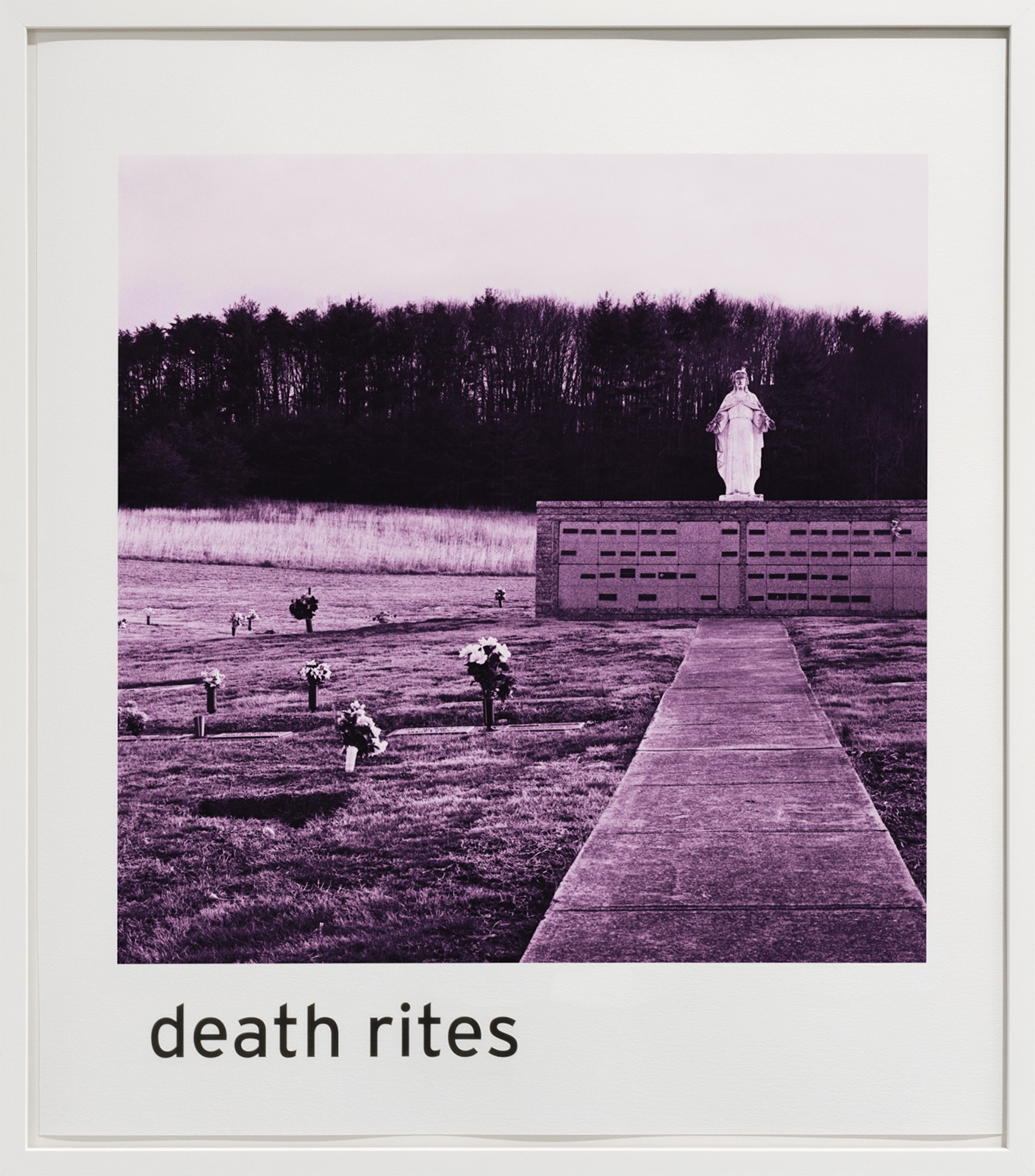

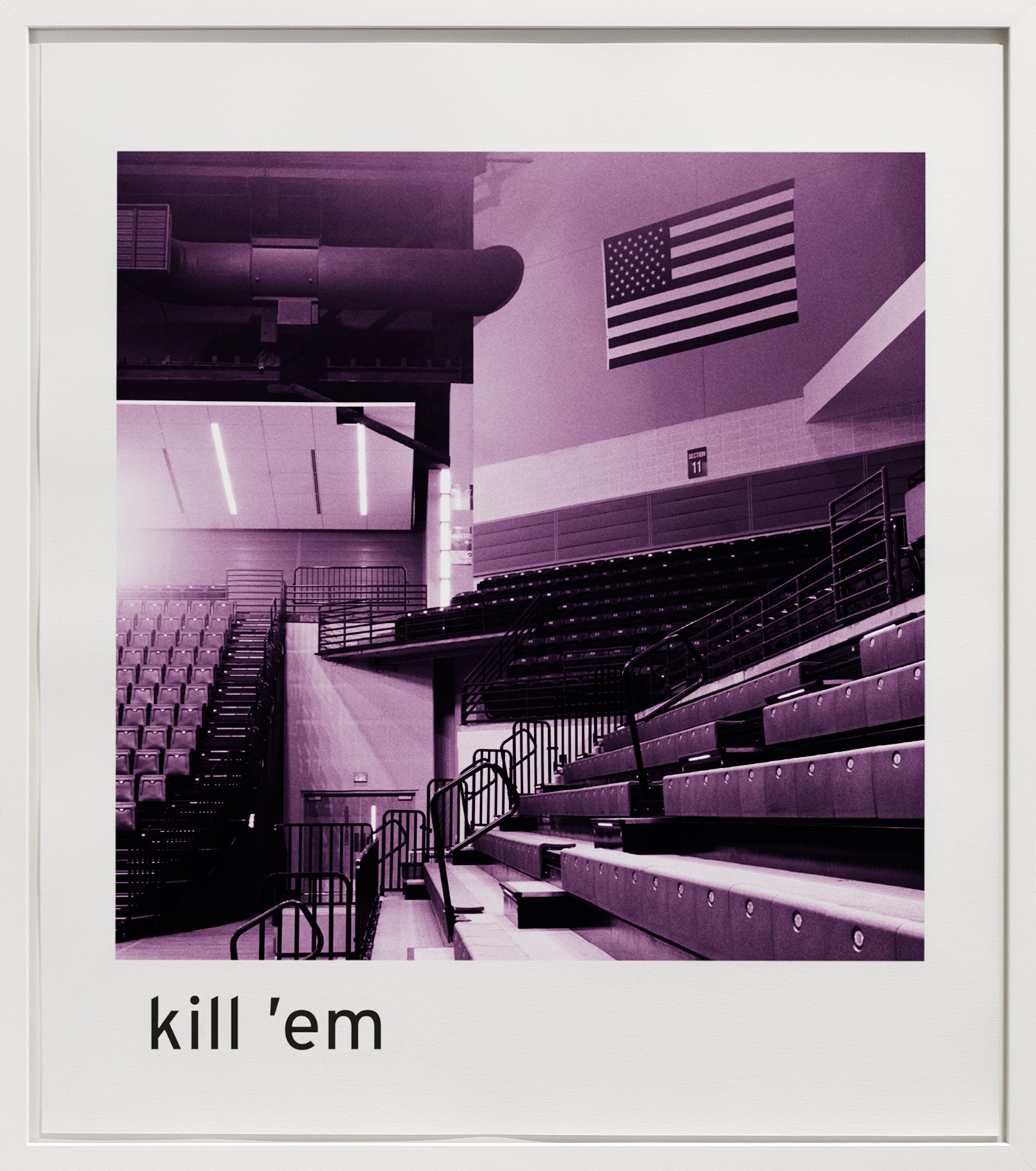

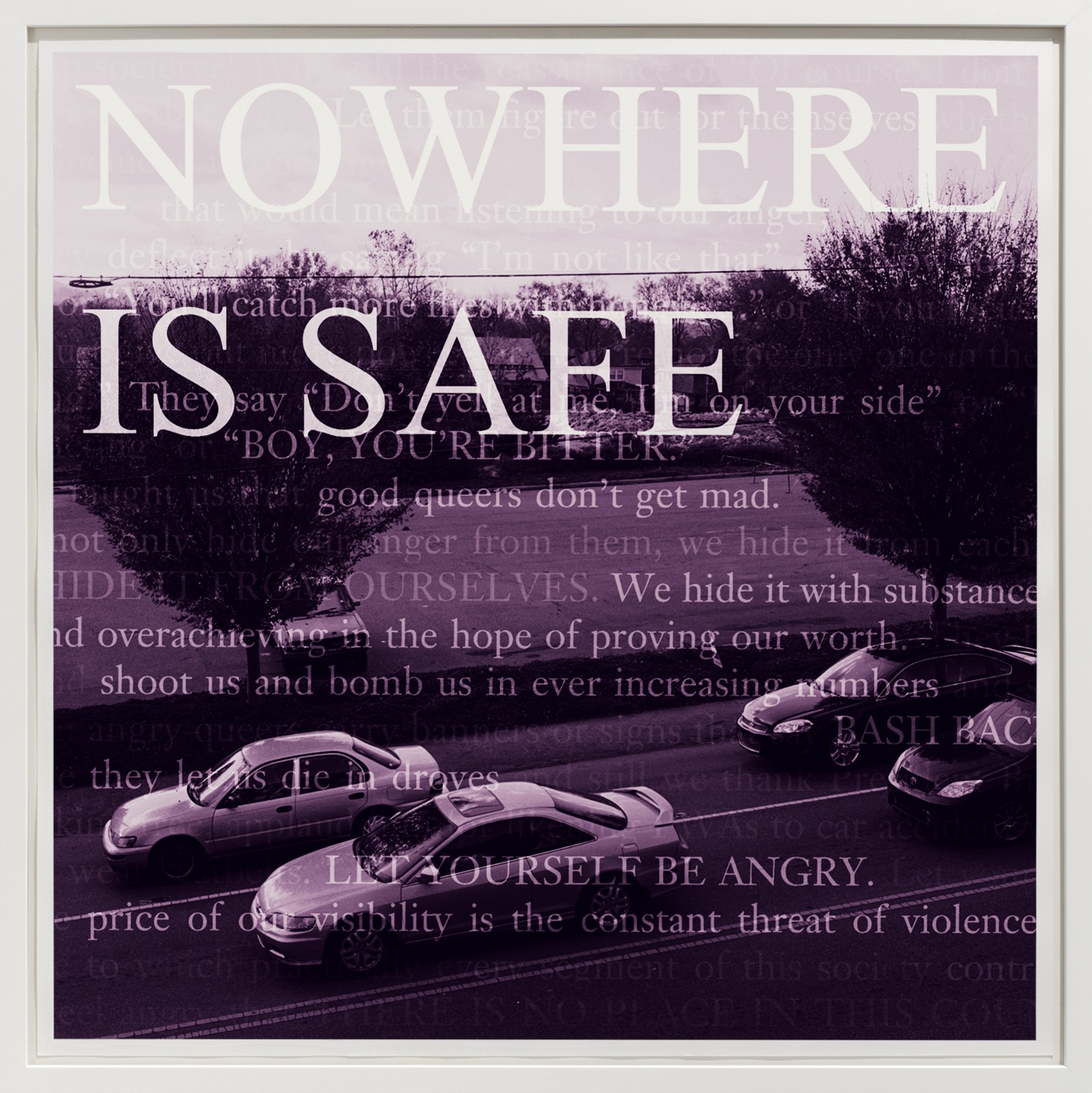

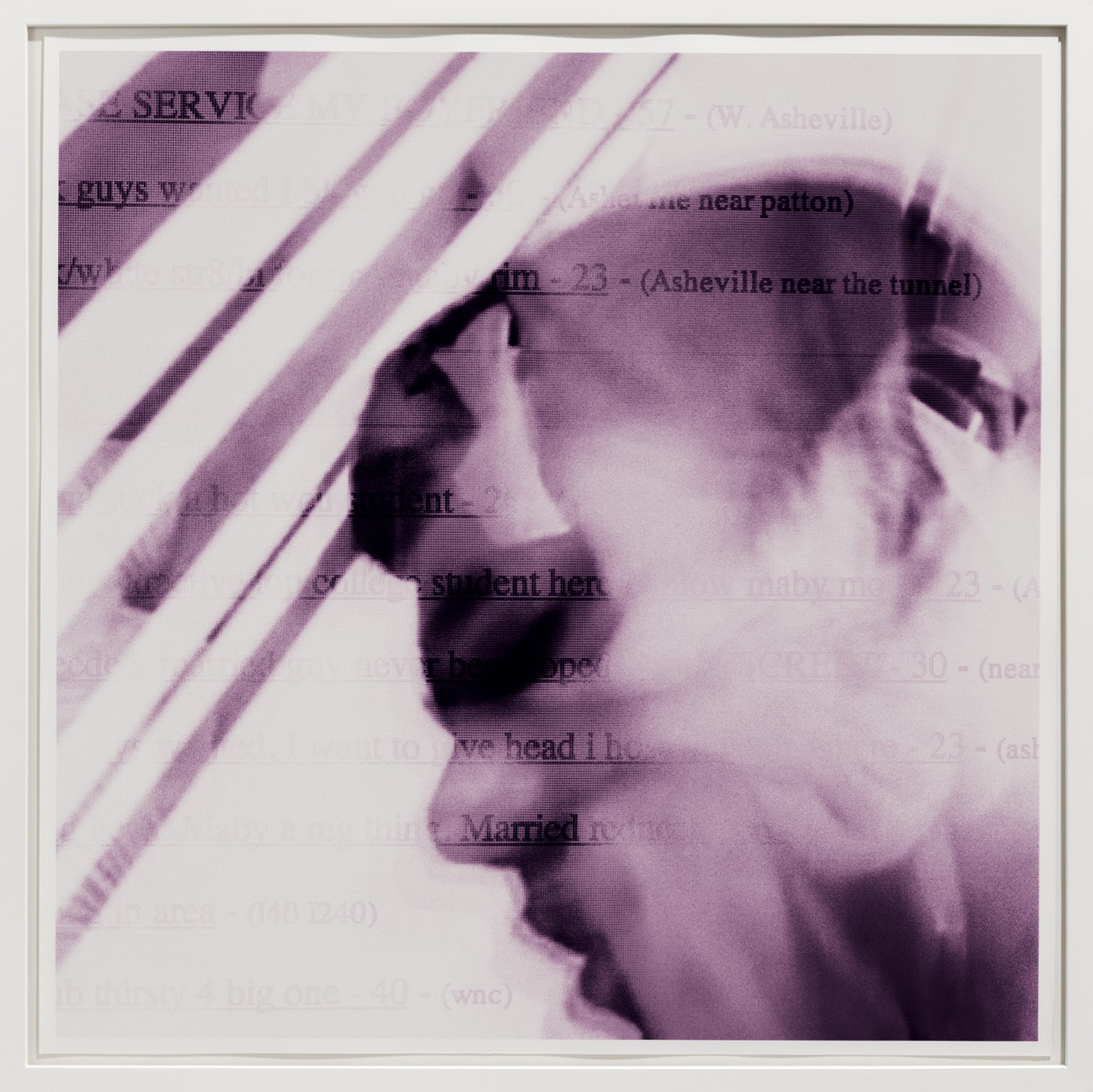

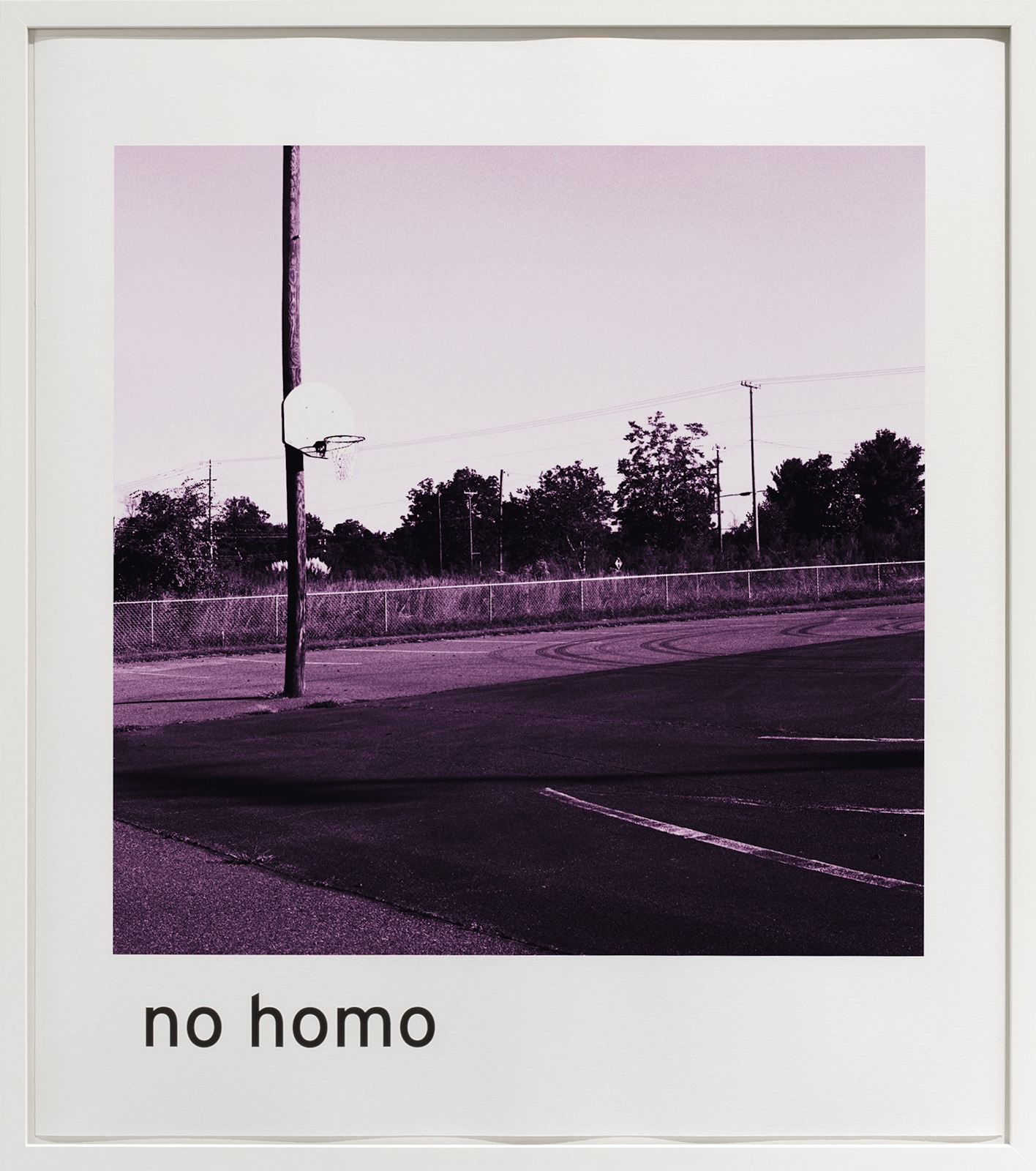

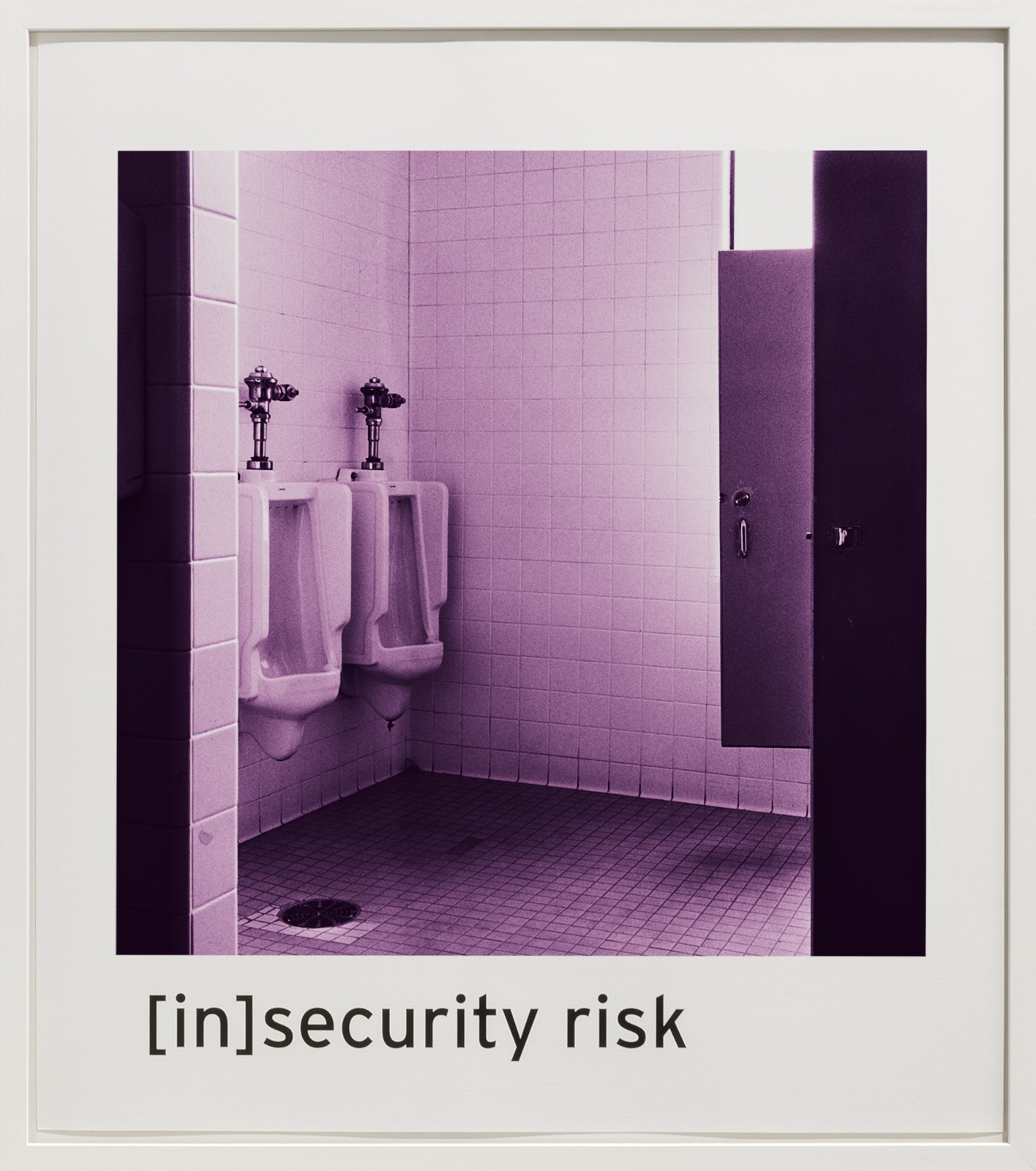

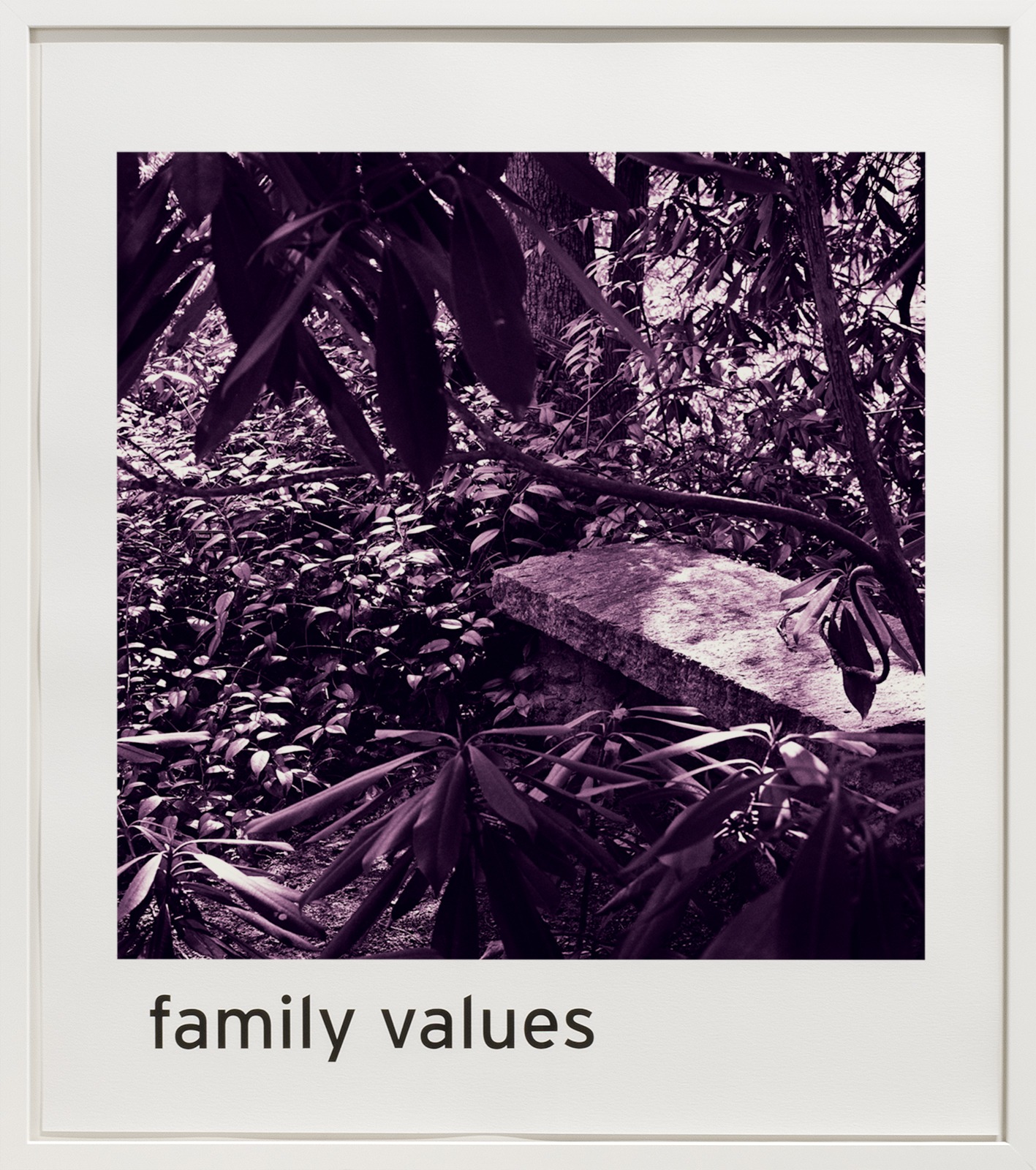

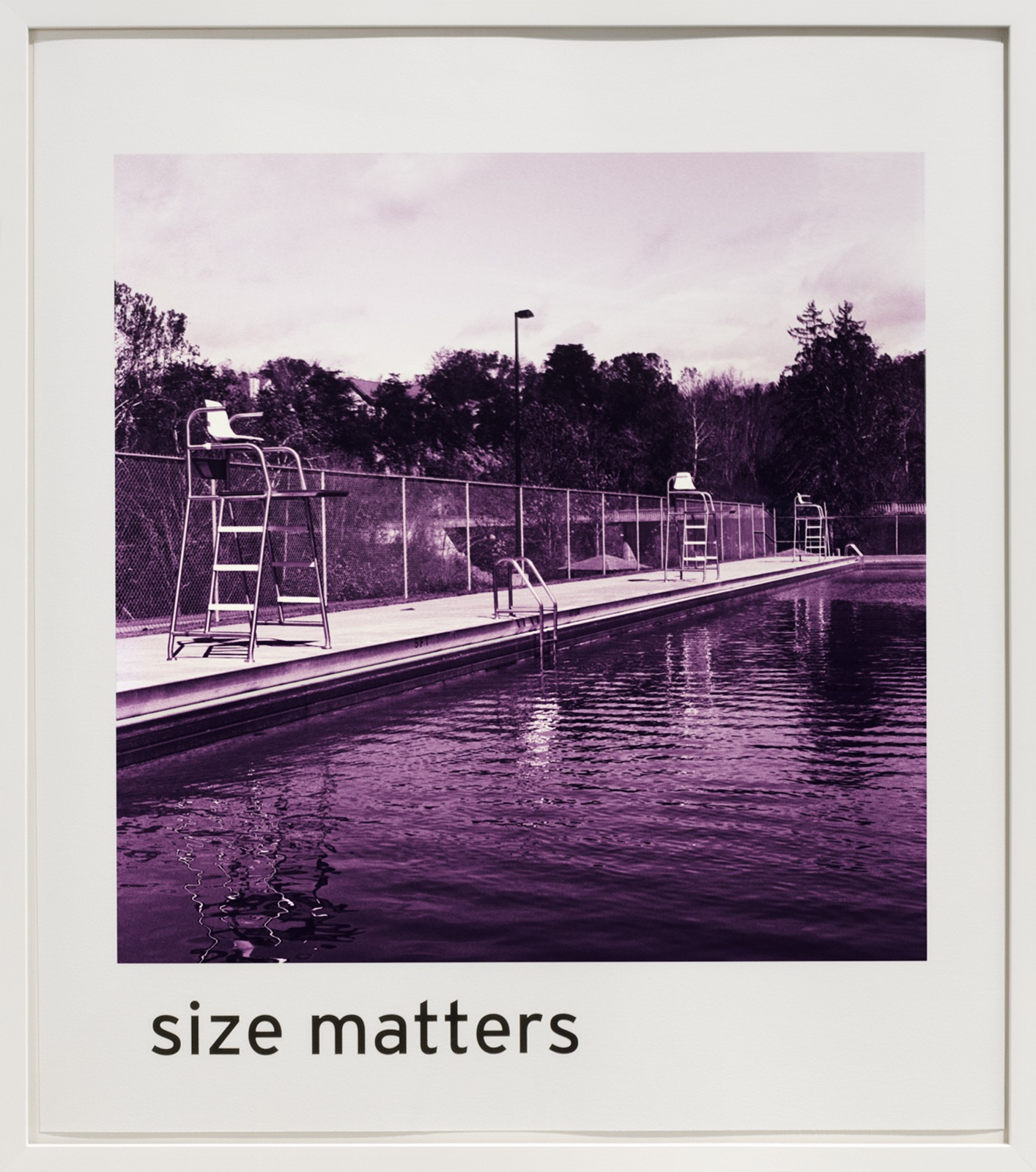

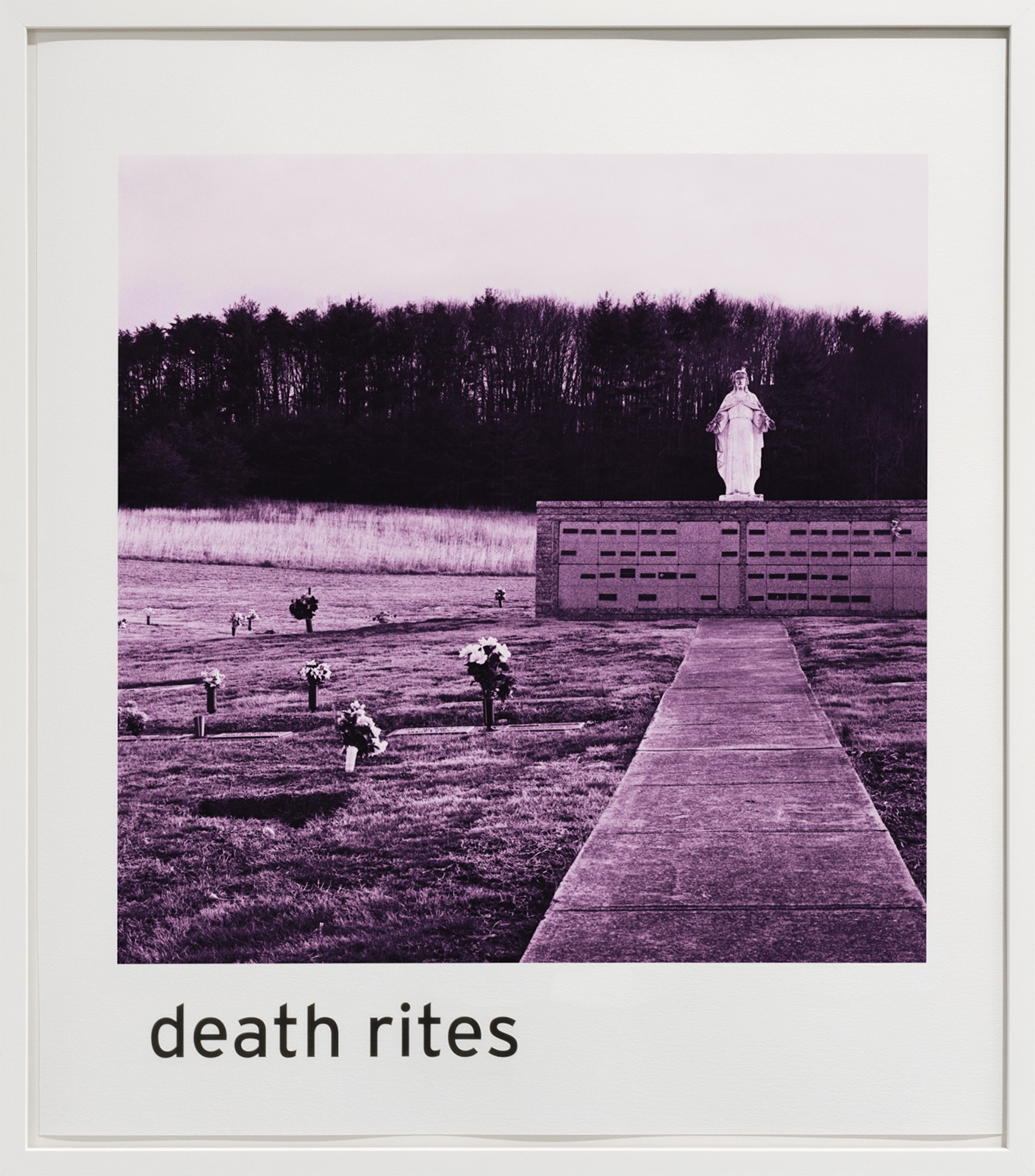

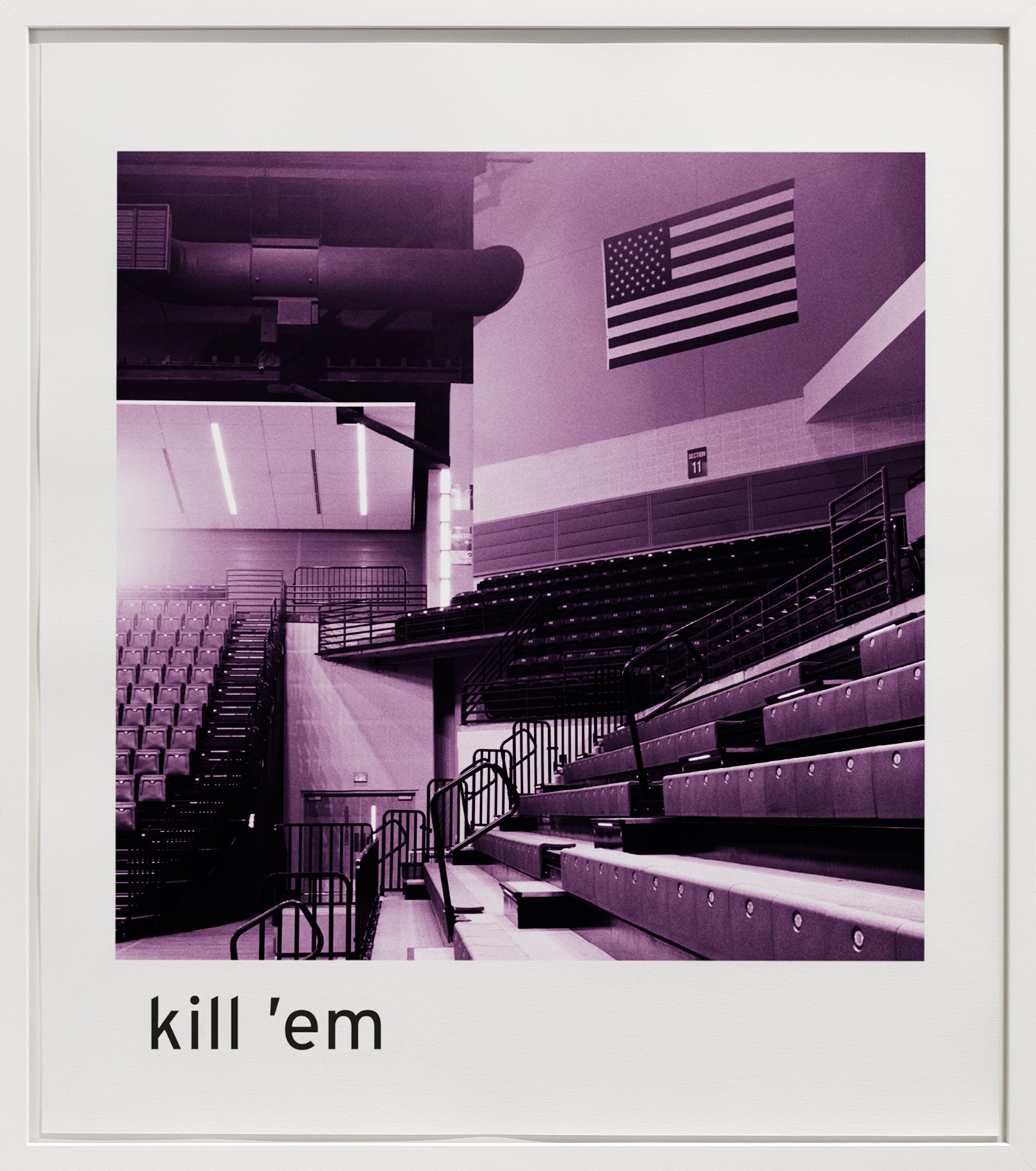

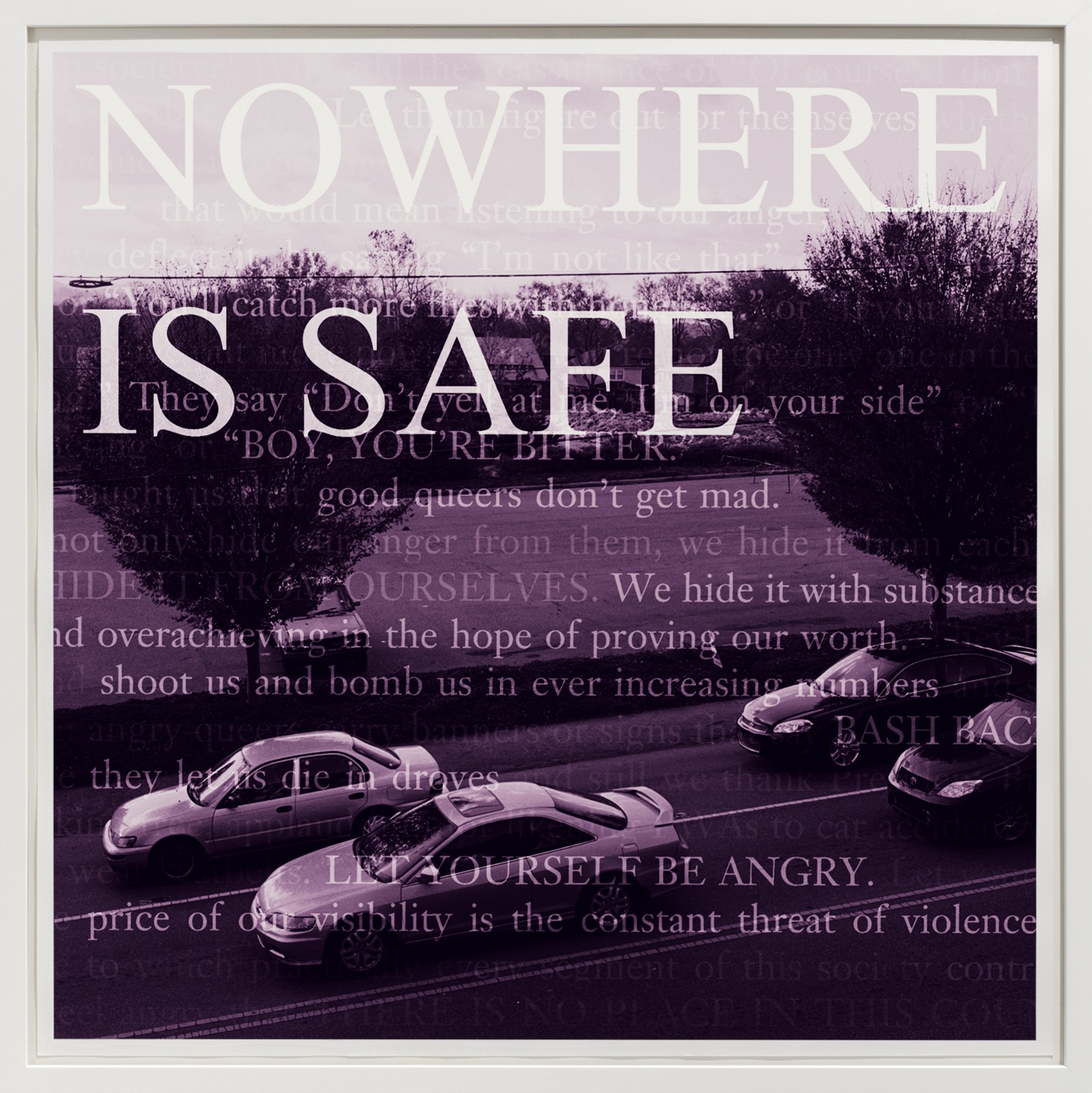

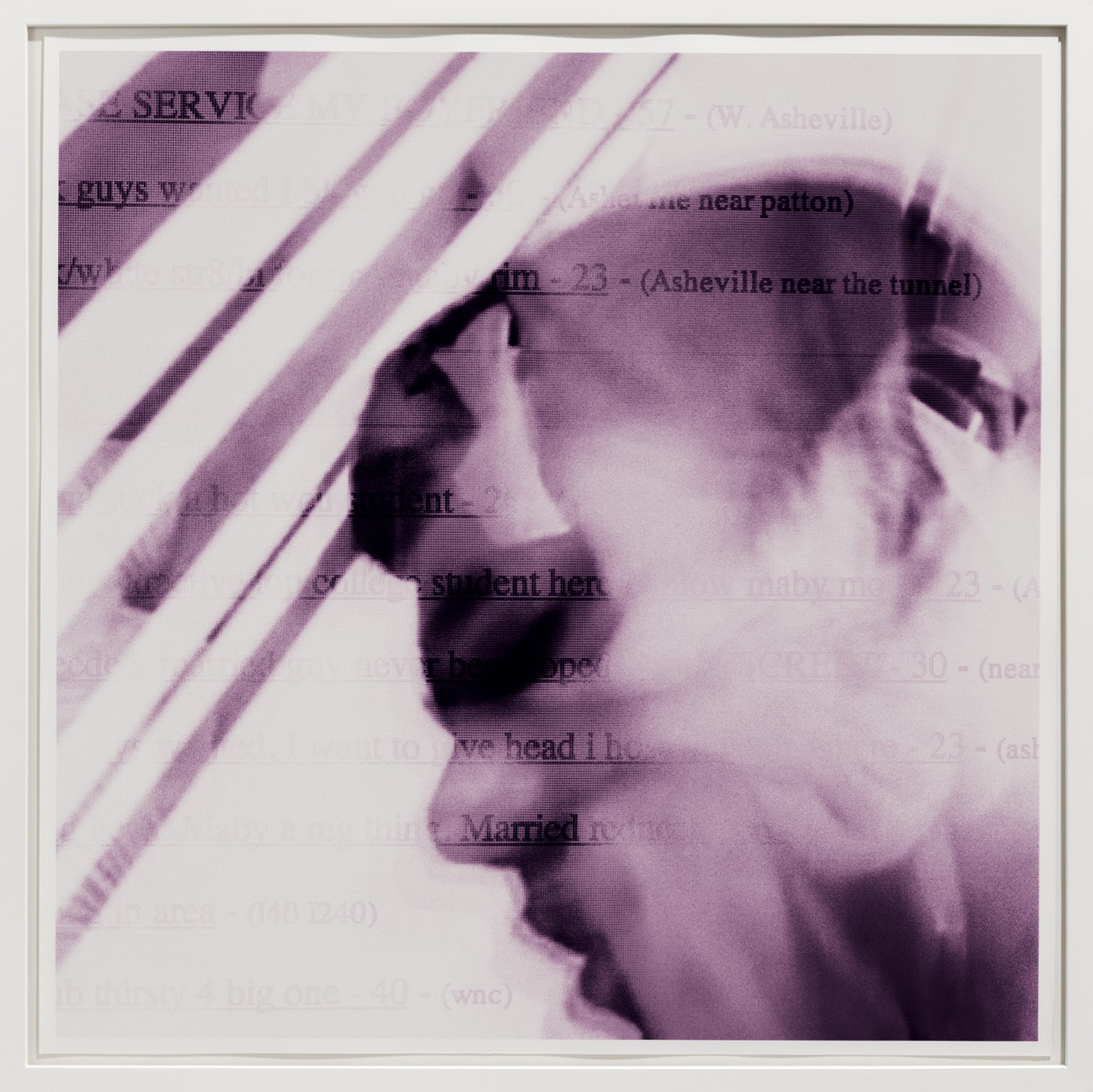

Lavender War (2013) was my undergraduate thesis project, exploring the ostracization of queer persons in public locations. This work began my ongoing research into how social and cultural values reside within the function and experience of everyday spaces. Toning black-and-white photographs to shades of purple and using overheard phrases found within the depicted environments, I intended to connect conversations from the (then-) present time to those of the 1950s and 60s when the “Lavender Scare” brought the concept of homosexuality fully into the mainstream. Much like the Red Scare, a witch-hunt for Communists in the United States, officials believed that these ‘deviants’ presented an urgent risk to social and national securities. The surrounding publicity initiated conversations that, for many Americans, were the first time they began to reckon with the existence of gays and lesbians, perhaps even within their own communities. The rapidly expanding reach of mass media only fueled the government-informed hysteria. These discourses contributed to modern legal and societal frameworks that actively privilege traditional (straight) nuclear families, rejecting those living outside of them.

These events played a role in my personal history, even decades later. Evangelical Christianity, the religion I grew up in, codified much of their rhetoric regarding gay and lesbian-identified people toward the end of this era as their own hyper-conservative movement began to gain traction. While creating this body of work, I negotiated the fallout from my personal coming out as gay and atheist a few years prior, losing my relationship with my family and lifelong community, due in part to a worldview informed by the social climate of the mid-20th century. As Arthur Warmoth wrote in Social Constructionist Epistemology, “people’s ideas are ultimately given meaning by their social context.” The use of narratives from my upbringing in the American South, and a visual survey of contested public spaces that often contain exclusionary language, demonstrate how power and context contribute to individual and community-based understandings of place. Expectations and moral values are not innate but instead constructed and shaped by predominant cultures and histories.

Lavender War (2013) was my undergraduate thesis project, exploring the ostracization of queer persons in public locations. This work began my ongoing research into how social and cultural values reside within the function and experience of everyday spaces. Toning black-and-white photographs to shades of purple and using overheard phrases found within the depicted environments, I intended to connect conversations from the (then-) present time to those of the 1950s and 60s when the “Lavender Scare” brought the concept of homosexuality fully into the mainstream. Much like the Red Scare, a witch-hunt for Communists in the United States, officials believed that these ‘deviants’ presented an urgent risk to social and national securities. The surrounding publicity initiated conversations that, for many Americans, were the first time they began to reckon with the existence of gays and lesbians, perhaps even within their own communities. The rapidly expanding reach of mass media only fueled the government-informed hysteria. These discourses contributed to modern legal and societal frameworks that actively privilege traditional (straight) nuclear families, rejecting those living outside of them.

These events played a role in my personal history, even decades later. Evangelical Christianity, the religion I grew up in, codified much of their rhetoric regarding gay and lesbian-identified people toward the end of this era as their own hyper-conservative movement began to gain traction. While creating this body of work, I negotiated the fallout from my personal coming out as gay and atheist a few years prior, losing my relationship with my family and lifelong community, due in part to a worldview informed by the social climate of the mid-20th century. As Arthur Warmoth wrote in Social Constructionist Epistemology, “people’s ideas are ultimately given meaning by their social context.” The use of narratives from my upbringing in the American South, and a visual survey of contested public spaces that often contain exclusionary language, demonstrate how power and context contribute to individual and community-based understandings of place. Expectations and moral values are not innate but instead constructed and shaped by predominant cultures and histories.

[/expander_maker]